Club Solo 2019

Michèle Matyn

[ENG]

Step into Michèle Matyn’s exhibition hall at Club Solo in Breda, and you’re faced with a moment of uncertainty. The characteristic contrast between the art space and everything outside of it is missing. There are some tables on the pavement outdoors, some cups here and there, a few people having a drink. Similarly, there are some people standing inside, a stretch of cloth has been draped across the room, two young boys are playing, some objects have been placed offhandedly here and there, with the same apparent carelessness as the cups on the tables outside. There’s a brief fade in the line between things ending up someplace by chance and things that are a little odd and different from our daily life. The room inside shows only a subtle shift from the world outside, a shift that sharpens the senses, eventually allowing you to perceive the idiosyncrasy in the details.

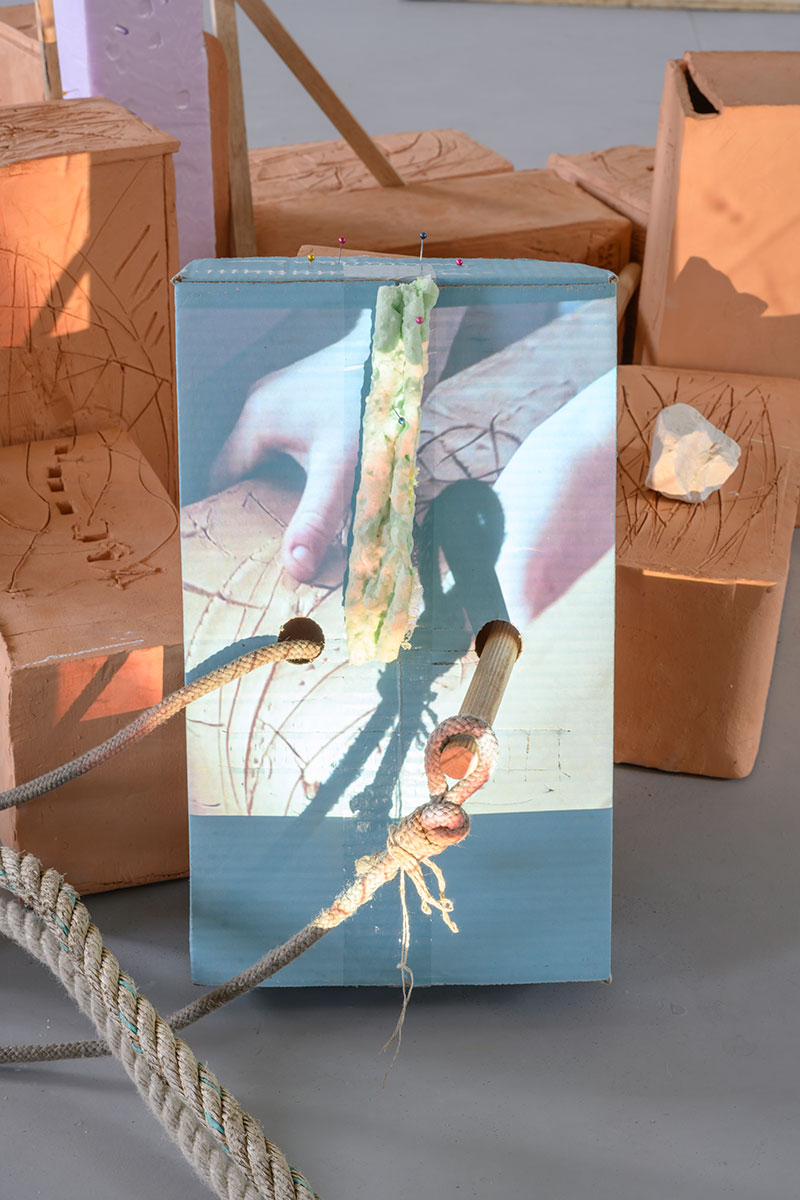

This hall is filled with all sorts of objects, scattered across the room freely, but certainly not randomly. A long piece of gleaming, rainbow-coloured cloth suggests a path through the hall passing by a range of things, including a pudding caudron overflowing with popcorn, little petrified tomatoes jutting out of the wall in places, ceramic thimbles that, when tapped together, serve as castanets. On both sides there are enlarged polaroid pictures printed on long strips of paper, showing imposing, mystical-looking, gnarled trees in ghostly colours. The middle of the path is marked by a big, lumpy slide that splits off, creating a Y shape. On one hand, the whole scene could be interpreted as the material traces of a wild outburst or a mysterious gathering that took place here, belonging perhaps to an eccentric cult, with new solemn rituals just around the corner. At the same time, considered separately, all elements, objects, constructions, lengths of rope, pieces of cork, and photographs are very recognisable – just like how you’d come across them in daily life, really. The space itself, the arrangement, is what charges everything with meaning.

Many of Michèle Matyn’s projects are linked to intensive travels to destinations near and far. Her almost nomadic way of life is an essential component of her work. She first made her adventurous journeys and hikes to the most desolate places, in the most extreme conditions, as a tourist – only later did she integrate that habit into her artist’s practice. With an anthropologist’s eye, she trekked from Canada, China and Northern Ossetia to Texas and Lapland, but didn’t skip her homeland Belgium either. As she travels, she observes people, habits, culture, customs, rituals, the landscape, and materials.

Her ‘anthropological’ observations are not scientific. Rather, they are coloured by her intimately personal experience of anything that she finds intruiging that may cross her path: her sensitivity to nature, her fascination for ancient folklore and customs, local myths and legends.

For Matyn, polaroid photography is an important medium, which she uses to record her observations. But unlike with documentary photography, Matyn’s polaroids are more of a reversal of the distant, neutral perspective. The characteristic warm colours and vague blurriness are the result of imperfections and happenstance that comes with the camera’s workings. And it’s this warping – the polaroid’s pictorial poetry – that Matyn embraces.

Observation and registration change in the process, influenced by her participation. She makes no effort whatsoever to distinguish between her personal fascinations, private life and professional work; all three are intricately bound together. Warping and observation are no longer separable components, but form a new whole, a chain of discoveries and interventions.

In 1934, American philosopher, psychologist and pedagogue John Dewey described how the aesthetic form, as captured by visual art, is only a moment of consolidation in a larger process of life: desiring, studying, obtaining and consolidation.

‘The juice expressed by the wine press is what it is because of a prior act, and it is something new and distinctive. It does not merely represent other things. Yet it has something in common with other objects and it is made to appeal to other persons than the one who produced it. A poem and picture present material passed through the alembic of personal experience.

Their material came from the public world and so has qualities in common with the material of other experiences, while the product awakens in other persons new perceptions of meanings of the common world. The oppositions of individual and universal, of subjective and objective (…) have no place in the work of art. Expression as personal act and as objective result are organically connected with each other.’ (1)

This description seems a fitting one for Michèle Matyn’s work and approach. For her Club Solo exhibition, the artist has drawn inspiration from the time she spent with her two young sons in a variety of travels, as she usually does. One of these was a three-month stay in Andalusia, where they lived as a three-member collective. Work, surroundings and (family) life were practically inextricable during this time. The direct physical environment of Andalusian nature and Spanish culture, alongside her daily life that went on throughout all this, all played a significant part in the development of the work. With their Y shape, the age-old cork oaks in the hillside are reminiscent of a figure raising its hands to the sky. At the same time, they form a kind of trinity: where two unite and go on as one, or where one splits off. ‘WhY?’ these trees seemed to ask Matyn. Responding to this question she tried to find answers in a direct interconnection with the material: through the trees, the clay, drawing and photography, and working and living with her sons.

The work is the result of an attitude towards direct surroundings, nature and culture, living together, rebuilding with found materials. The exhibition space is a reflection of this process, with all senses being stimulated. The material study in clay, pudding, fabric, foam is brimming with references, not just to nature and its materials, but also to the Spanish catholic culture with regard to the devotion of Mary. The ritual culture surrounding Our Lady of Sorrows smoothly integrates in the hodgepodge of this space, which even includes local history of the city of Breda.

Move on to the first floor, and this all becomes clear. As she explored the city and its history, Matyn stumbled upon the historic incident from the Eighty Years’ War, when in 1590 Maurice of Nassau managed to recapture Breda from the Spaniards holding the city at the time, using a ruse. As if employing a real Trojan horse, he led a peat barge beyond the city walls, its hull full of soldiers, who were able to overpower the Spanish troops at night. Breda Castle, which garrisoned the Spanish troops, received regular shipments of peat. Arriving so frequently, the ship was no longer checked, and the skipper managed to smuggle the army inside.

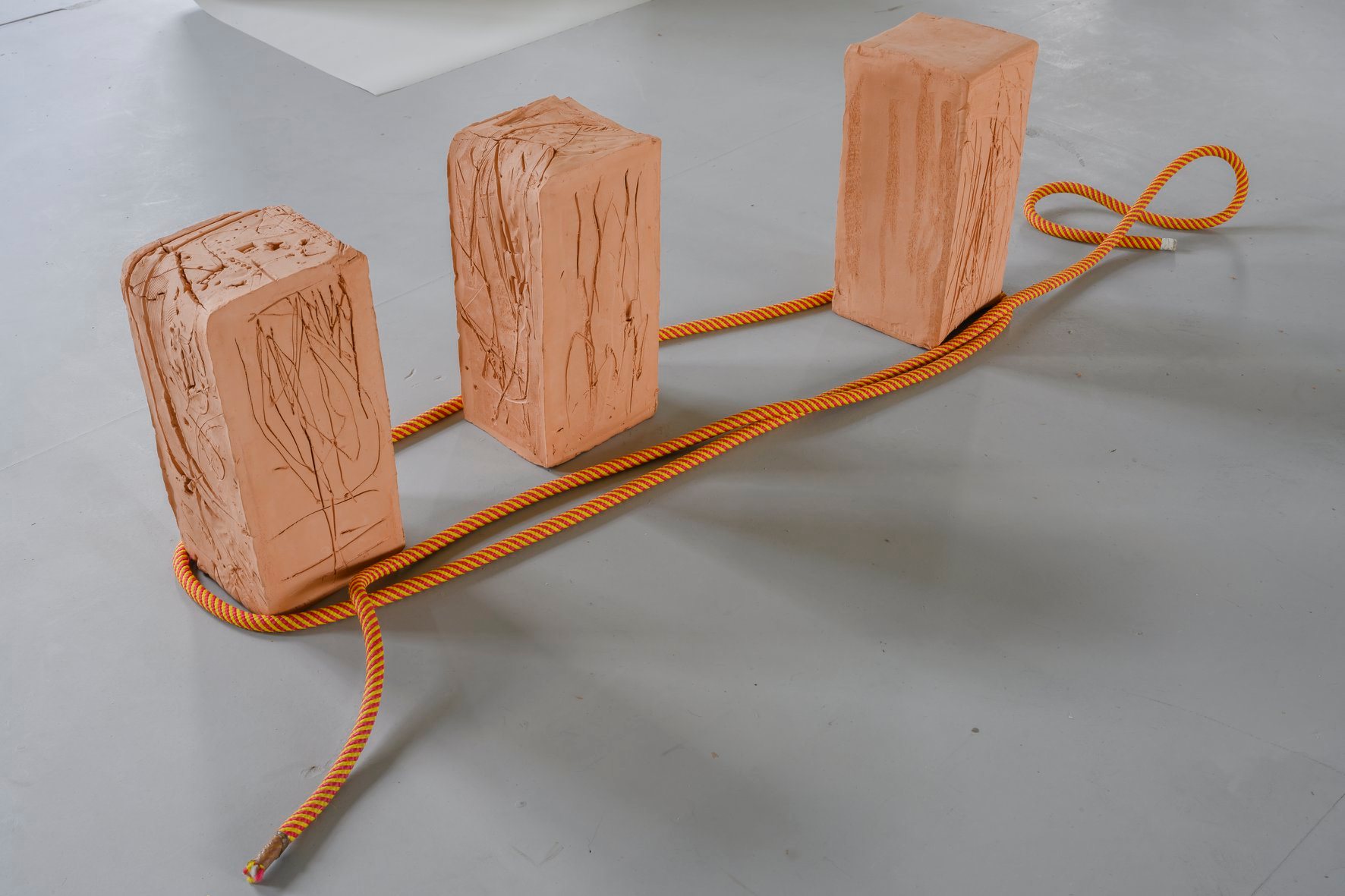

It doesn’t seem to be a coincidence that Matyn would be attracted by this story. Peat is a material that physically carries history inside of it. It is formed over a period of hundreds of years from dead plants in swampy marshes, creating layers of several metres. Those were then carved out and dug up. Man and nature left their mark; the soggy material was dried so the soil could be literally burnt for heating, cooking or forging. The first-floor hall is full of brick shells made by Matyn for the absent peat bricks. The original peat bricks formed a sort of imaginary mould for these bricks. The mould is all that’s left after being fired. In this case, the physical shape of the peat determined the shape of the hollow bricks, leaving an imprint, a trace of what once was.

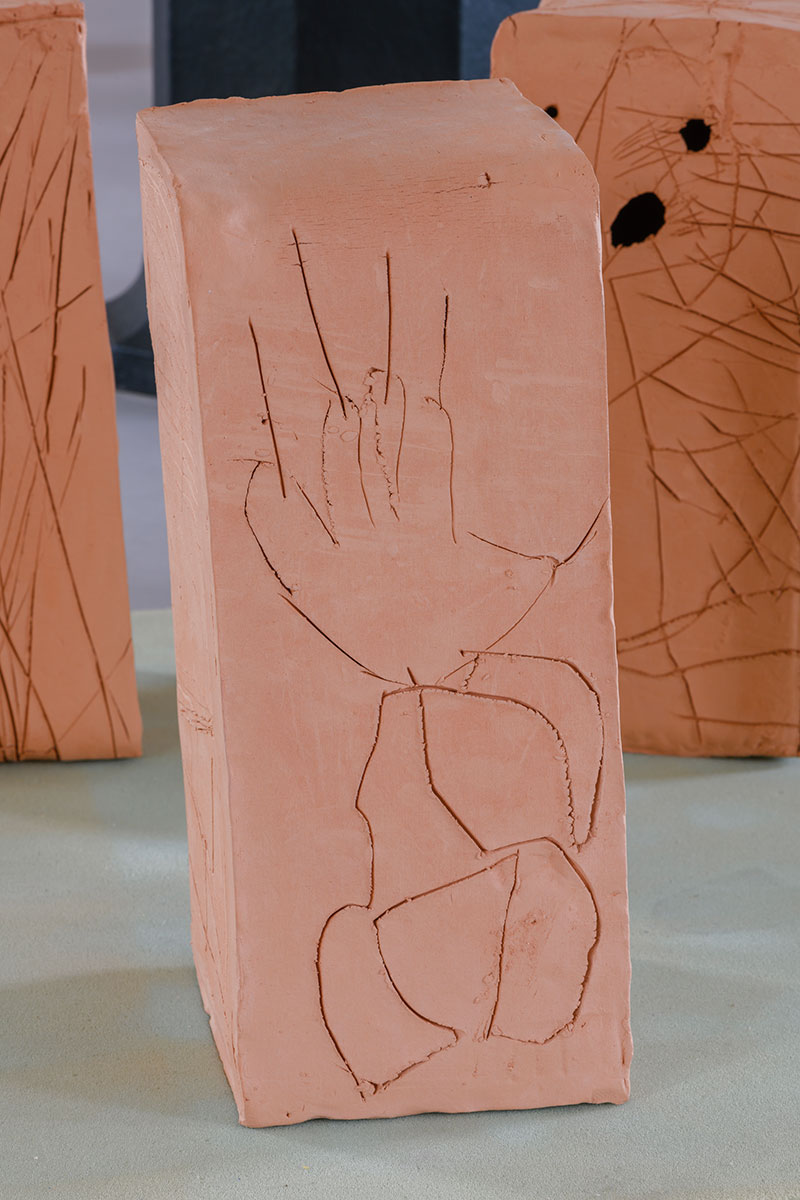

The brick boxes, in turn, brought about new encounters and served as material for new explorations. During another journey Michèle took to Finland, she discovered decades-old, sometimes centuries-old inscriptions in coastal rocks. There were highly detailed, expertly carved signs, including hearts, anchors, dates, and messages in mysterious codes adorning the rocks, giving them the appearance of a petrified torso of a fully tattooed sailor. Were seafarers leaving messages for the ones they loved and missed, or were these the heartfelt cries of the ones left behind? Inspired by the sight, Ewoud and Bernhard, Matyn’s two sons, went to work on the still unhardened clay of the brick shells, which they diligently decorated with drawings and messages of their own, ranging from hair jellyfish to a sunrise, using signs that only seem to carry meaning to those in the know.

The room shows the traces and remains of a continuous process of finding, processing, crafting, interpreting, and migrating, transforming by Matyn and her loved ones. You get a welcome feeling as a visitor, as if you’re invited to join a vibrant environment where Ewoud and Bernhard storm the path disguised as rainbow heroes, eat from the popcorn jar, and build ships out of the bricks when their fancy takes them. This room is about more than a purely physical process. The material, ideas and photographs together create a new, but hard to define significance.

In his plea against the separation of the aesthetic experience from the rest of daily life, John Dewey touches right upon the crux of the experience taking place here: ‘There are meanings that present themselves directly as possession of objects which are experienced. Here there is no need for a code or convention of interpretation; the meaning is as inherent in immediate experience as is that of a flower garden.’ (2)

The matters of the mind, often considered ‘above’ all else, the philosopher says, aren’t purely elevated to another realm, but rather go hand in hand with everyday, earthly, physical matters. To him, the aesthetic, physical experience was a component of a greater process of life, acting as a source that charges more sensual, directly experienced material matters with meaning: ‘There is no limit to the capacity of immediate sensuous experience to absorb into itself meanings and values that in and of themselves would be designated “ideal” and “spiritual”.’ (3)

Y? It’s not a question for Matyn to mull over for too long. She lets herself get carried along with the continuous flow of encountering, appropriating, transforming, and getting distracted again by what crosses her path. ‘We find the answers through the things we make,’ seems to be Matyn’s response.

Notes

1 John Dewey. Art as Experience. The Berkeley Publishing Group, New York, 1934, ed. 2005, p. 86

2 idem, p. 87

3 idem, p. 5

text: Dyveke Rood

http://clubsolo.nl/en/zomerstop/

[NL]

Wanneer je de tentoonstellingsruimte van Michèle Matyn bij Club Solo in Breda binnengaat, is er even onzekerheid.

De scherpte van het contrast tussen kunstruimte en alles wat daar, ontbreekt hier. Buiten staan wat tafeltjes op de stenen bestrating, wat kopjes hier en daar, enkele mensen die wat drinken.

Ook binnen staan wat mensen, er is een doek gedrapeerd door de ruimte, twee kleine jongens spelen, hier en daar zijn wat kleine objecten nonchalant uitgestald, schijnbaar net zo achteloos als de kopjes buiten op tafel. De grens tussen wat per ongeluk ergens is beland en wat een beetje vreemd en anders is dan het dagelijkse leven, blijft voor een moment onduidelijk. De ruimte binnen is slechts een subtiele verschuiving ten aanzien van de wereld erbuiten; een die de zintuigen verscherpt en waardoor je na enige tijd de eigenzinnigheid in de details waarneemt.

Deze ruimte is gevuld met allerlei objecten, losjes verspreid door de hele ruimte maar toch verre van willekeurig gearrangeerd. Een lang stuk glanzend en regenboogkleurig doek suggereert een parcours door de ruimte die leidt langs allerhande zaken, zoals een puddingpot overladen met popcorn, versteende tomaatjes die hier en daar uit de muur steken, keramieken vingerhoedjes die, als je ze tegen elkaar tikt, fungeren als castagnetten.

Aan weerszijden hangen, geprint op lange stroken papier, uitvergrote polaroids van imponerende en mystiek ogende knokige bomen in schimmige kleuren. Midden op de route staat een grote bobbelige glijbaan die zich in tweeën splitst, waardoor er een Y-vorm ontstaat. Het geheel laat zich aan de ene kant lezen als een materieel spoor van een wilde uitspatting of van een mysterieuze bijeenkomst die hier heeft plaatsgevonden, misschien van een zonderlinge sekte, waar ieder moment plechtige rituelen kunnen plaatsvinden.

Tegelijkertijd zijn alle afzonderlijke elementen, objecten, bouwsels, touwen, stukken kurk en foto's heel herkenbaar, zoals je ze in het dagelijks leven ook regelmatig tegenkomt. Het is de ruimte zelf, het arrangement dat alles een zekere geladenheid geeft.

Veel projecten van Michèle Matyn gaan gepaard met intensieve reizen. Haar haast nomadische bestaan naar verre en nabije oorden zijn een essentieel onderdeel van haar werk. De avontuurlijke reizen en wandeltochten naar de meest desolate plekken en onder extreme omstandigheden, ondernam zij eerder al als toerist, een gewoonte die zij later integreerde in haar kunstenaarspraktijk. Van Canada, China, Noord-Ossetië tot Texas en Lapland, maar ook binnen haar thuisland België is zij getrokken met een haast antropologisch oog. Al reizende observeert ze mensen, gewoonten, cultuur, gebruiken, rituelen, landschap en materialen. Haar zogenaamde antropologische observaties zijn niet die van een wetenschapper maar worden gekleurd door haar intens persoonlijke beleving: haar gevoeligheid voor de natuur, fascinatie voor eeuwenoude volksverhalen en gewoonten, locale mythen en sagen, door alles wat op haar pad komt en haar intrigeert.

De polaroid foto is een belangrijk medium voor Matyn waarmee zij haar observaties vastlegt. Maar anders dan in de documentaire fotografie zijn de polaroids voor Matyn eerder een omkering van het afstandelijke en neutrale standpunt. De typisch warme kleuren en de wazige onscherpte zijn het gevolg van imperfecties en toevalligheden, eigen aan het automatisme van de camera. Precies deze vervorming - de picturale poëzie van de polaroid - omarmt Matyn. Observatie en registratie veranderen gedurende het proces, beïnvloed door haar deelname. Zij doet geen enkele moeite haar persoonlijke fascinaties, privéleven en professioneel werk te scheiden, maar deze zijn intens met elkaar vervlochten. De vervorming en observatie zijn niet langer uit elkaar te halen en worden één geheel, een aaneenschakeling van vondsten en ingrepen.

In 1934 beschreef de Amerikaanse filosoof, psycholoog en pedagoog John Dewey hoe de esthetische vorm, zoals gevangen in de beeldende kunst, slechts een kort moment van consolidatie is in een groter proces van leven: verlangen, onderzoeken, verkrijgen en consolideren.

“The juice expressed by the wine press is what it is because of a prior act, and it is something new and distinctive. It does not merely represent other things. Yet it has something in common with other objects and it is made to appeal to other persons than the one who produced it. A poem and picture present material passed through the alembic of personal experience. Their material came from the public world and so has qualities in common with the material of other experiences, while the product awakens in other persons new perceptions of meanings of the common world. The oppositions of individual and universal, of subjective and objective (…) have no place in the work of art. Expression as personal act and as objective result are organically connected with each other.”

Deze omschrijving lijkt precies het werk en de benadering van Michèle Matyn te passen. Ook voor de tentoonstelling in Club Solo heeft de kunstenaar zich laten inspireren door de verschillende periodes die zij samen met haar twee zoontjes op verschillende reizen heeft doorgebracht. Een daarvan vond gedurende twee maanden plaats in Andalusië. Hier werkten en leefden zij als een drieledig collectief, waarbij opnieuw werk, omgeving en (familie)leven lastig te ontwarren waren. De directe fysieke omgeving van de Andalusische natuur, de Spaanse cultuur en haar dagelijks leven dat zich hier temidden afspeelde hebben het werk mede vormgegeven. De Y-vormen van de eeuwenoude kurkeiken die heuvels bekleden, hebben de gedaante van een figuur die de handen omhoog slaat. Tegelijk is het een soort drie-eenheid: waar twee samenkomen en als een verder gaan, of waarin een zich opsplitst. ‘WhY’? vroegen deze kronkelende bomen aan Matyn. Zij pakte de vraag op en probeert antwoorden te vinden in de directe verbinding met het materiaal: de bomen, de klei, via het tekenen en fotograferen, en via het werken en leven met haar zoontjes.

Het werk komt voort uit een omgaan met de directe fysieke omgeving, de natuur en cultuur, het leven met elkaar, het opnieuw bouwen met gevonden materiaal. De ruimte is een weerspiegeling van dit proces, waarin alle zintuigen worden geprikkeld. Een materiaalonderzoek met klei, pudding, textiel, schuim is doorspekt met talloze referenties, niet alleen naar de natuur en het materiaal, maar ook naar de Spaanse Mariavererende cultuur. De rituele cultuur die de Maria van de Smarten omgeeft, laat zich naadloos verenigen met deze mengelmoes, waarin ook de locale Bredase geschiedenis wordt opgenomen.

Wanneer je naar de tweede verdieping loopt, wordt dit duidelijk. Struinend door stad en geschiedenis stuitte Matyn op het historische voorval uit de Tachtigjarige oorlog, waarbij Maurits van Nassau in 1590 met een list Breda wist te heroveren op de Spanjaarden die de stad op dat moment onder hun bewind hadden. Als een Trojaans paard leidde de graaf een turfschip de stad binnen met een buik vol met soldaten die ’s nachts de Spaanse troepen wisten te overmeesteren. De schipper vervoerde regelmatig turf naar het Kasteel van Breda, waar de Spaanse troepen gelegerd waren. Omdat hij zo vaak kwam, werd zijn schip niet meer gecontroleerd en wist zo het leger binnen te smokkelen.

Het lijkt geen toeval te zijn dat Matyn zich tot dit verhaal voelt aangetrokken. Turf is een materiaal dat op fysieke wijze geschiedenis in zich draagt. Turf vormt zich over een periode van honderden jaren uit afgestorven planten in de moerassige veengebieden tot een metersdikke veenlaag. Die werd vervolgens weggestoken en opgebaggerd. Mens en natuur hebben hun sporen achtergelaten, het sompige materiaal werd gedroogd en de aarde werd vervolgens letterlijk verbrand om de huishoudens warm te houden, om mee te koken of te smeden.

De zaal op de tweede verdieping is gevuld met de bakstenen omhulsels die Matyn voor de verdwenen turfbroden heeft gemaakt. De oorspronkelijke turfbroden vormden als het ware een imaginaire mal voor deze bakstenen. Eenmaal gebakken, resteert de mal. De fysieke vorm van het turf bepaalde in dit geval de vorm van de holle bakstenen, een afdruk gevend, een spoor achterlatend van wat er was.

De bakstenen kisten waren op hun beurt weer aanleiding voor nieuwe ontmoetingen en dienden als materiaal voor verdere verkenningen. Op een andere reis die Michèle naar Finland maakte, ontdekte ze aan de kust decennia oude, soms eeuwenoude inscripties in de rotsen. Het zijn zeer gedetailleerd en ambachtelijk gegraveerde tekens, zoals harten, ankers, jaartallen en berichten in mysterieuze codes die de rotsen versieren gelijkend een versteende torso van een vol getatoeëerde zeebonk. Lieten zeevaarders daar berichten achter voor hun geliefden en gemisten, of waren het de hartekreten van de achterblijvers? Hierdoor geïnspireerd zijn Ewoud en Bernhard, de twee zoontjes van Matyn, aan de slag gegaan met de nog zachte klei van de bakstenen omhulsels die zij ijverig hebben betekend met hun eigen tekeningen en berichten, uiteenlopend van haarkwallen tot zonsopgang en tekens die alleen voor intimi betekenis lijken te dragen.

De hele ruimte toont sporen en resten van een continu proces van vinden, verwerken, bewerken, interpreteren, verhuizen en transformeren tot iets nieuws door Matyn en de haren. Als bezoeker voel je je welkom, alsof je mee mag doen in een zeer levende omgeving waarin Ewoud en Bernhard, wanneer zij de zin voelen, vermomd als regenbooghelden het parcours bestormen, de glijbaan beklimmen, onderweg uit de popcornpot eten en schepen bouwen van de bakstenen. Deze ruimte toont niet alleen een puur fysiek proces. Het materiaal, de vondsten en de foto’s creëren met elkaar een nieuwe, maar moeilijk grijpbare lading.

In zijn pleidooi tegen de scheiding van de esthetische ervaring van de rest van het dagelijks leven, beschrijft John Dewey precies de crux van de ervaring die hier plaatsvindt:

“There are meanings that present themselves directly as possession of objects which are experienced. Here there is no need for a code or convention of interpretation; the meaning is as inherent in immediate experience as is that of a flower garden.”

De vaak als ‘verheven' beschouwde geestelijke zaken zijn volgens de filosoof niet puur verheven en van een andere wereld, maar gaan hand in hand met de alledaagse aardse, lichamelijke zaken. Voor hem was de esthetische, fysieke ervaring onderdeel van een groter proces van leven, dat de bron is die de meer zinnelijke materiële zaken laadt met een directe ervaring van betekenis:

“There is no limit to the capacity of immediate sensuous experience to absorb into itself meanings and values that in and of themselves would be designated 'ideal and 'spiritual'.”

Y? Het is niet een vraag waar Matyn lang bij kan blijven stil staan. Zij laat zich meevoeren in de continue stroom van aantreffen, toe-eigenen, transformeren en zich weer verder laten leiden door wat op haar pad komt. ‘Middels de dingen die we maken vinden we de antwoorden’ lijkt de respons van Matyn te zijn.

tekst: Dyveke Rood